Shale Bonanza or Damp Squib for the UK? Part 2

Alan Tootill continues to examine what shale gas holds for our future

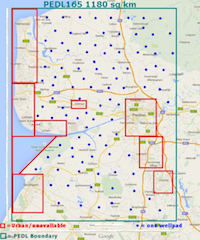

5. Cuadrilla’s ambition in PEDL165 (Fylde and West Lancs)

In 2011 Cuadrilla estimated there was 200 tcf in their PEDL “patch”. If that is true, how much will they extract?

Cuadrilla boss Francis Egan recently talked about 100 pads over 30 years. Assuming they haven’t changed their mind yet again this week, we’ll work on the basis of each pad having 12 verticals each sprouting up to three horizontals. Counting every horizontal as a well for calculation purposes let’s apply the IoD 3.16 bcf per well.

This gives up a total output of 100 x 12 x 3 x 3.16 bfc. 11,376 bcf or 11.4 tcf (I’ll round generously in their favour).

This implies an ultimate recovery factor of only 5.7%. To achieve 10% recovery of gas in place as Egan hopes would require each well to have an EUR of 5.54. Not impossible, perhaps, but given that according to the USGS in 2012 the best performing US field – Haynesville – had a mean EUR of less than half that, 10% looks optimistic indeed. What is remarkable about the US figures is the variation between wells, in Haynesville, for example, the maximum EUR estimate for a well was 20 bcf, but the minimum was a mere 0.02bcf, two orders of magnitude smaller. The mean was 2.62 bcf. And remember this was the best performing field.

In this case, because Cuadrilla would be pretty much covering all their patch with 100 pads, there seems no way they can improve on this. At one time they estimated 120 pads with ten verticals per pad, this comes to the same total number of wells and doesn’t affect the above figures.

6. How do the new BGS estimates affect Cuadrilla?

Not a lot, probably.

We are working on the assumption that a pad covers roughly 4 square miles of “below ground” area, with horizontals about a mile long. The Cuadrilla PEDL165 is in total 468 sq miles. We have to deduct from that the built-up areas of the Fylde coast from Fleetwood to Lytham, Preston, Chorley, Southport and other towns. It is surprising, frankly, that Cuadrilla can even envisage 100 pads in the countryside. This probably means in effect that their horizontal outreach from each pad will be smaller, with a resulting reduction each horizontal’s possible EUR.

Cuadrilla described their 2011 estimate of 200tcf as “conservative”. It is not immediately clear from the new BGS estimates how much of the new gas in place for the North estimate of 1329 tcf would apply to Cuadrilla’s patch. Let us suppose for argument sake it is double Cuadrilla’s estimate and there is 400tcf under PEDL165. How is Cuadrilla to extract that? There is no room for more pads, so to exploit more gas can only mean more laterals per vertical. 8 laterals per vertical drilling? An incredible leap in technology.

The more gas they estimate is in a heavily populated area like the UK, does not help them. They can’t get it out. And how does the fact that the assessed region includes heavily built up areas? The gas has been down there trapped in the rock for eons. It is not suddenly going to migrate from under Preston or Blackpool to rural Fylde because wells have been drilled there. It is not accessible.

It is simply not feasible to think of drilling horizontals under urban areas. It is one thing having rural residents accepting wells drilled under their land, entirely different to get an urban population to accept this. And there are legal reasons. Every horizontal drilled must have the consent agreed with the owner of every patch of land under which the horizontal is bored. Of course landowners do not own any oil or gas under their land, the government does, but they do have legal access and underground wayleave rights.

This would, in fact, seriously affect the possibility of Cuadrilla achieving its 100 pad plan. Unless, of course, the government strips landowners of all their rights. This would in our view cause a serious backlash throughout the country.

7. Effects of Cuadrilla’s plan.

On the generous scenario 1 outlined in part 1 and following the guidelines above, the main point is that Cuadrilla will only extract a limited amount of gas, however much is available. 11.4 tcf is only 3 years or so of UK gas consumption. Spread over 30 years, or more, this is very little reward.

How can Cuadrilla increase the return? The main point is that shale gas wells have a depressingly high decline in production rates from the time they are fracked. There is a very high decline in the first year (up to around 80%), and an exponential decline thereafter. As mentioned previously, this may mean half a well’s production is achieved in the first five years.

There are perhaps two ways this could be tackled. The first is by re-fracking each well on a regular basis, to boost production for another short period. It’s said some US wells have been fracked many times, but difficult to find evidence of this.

The second way of increasing production is simply digging more wells. For new horizontals to go where the previous ones haven’t reached. This raises a future scenario of many more wells than Cuadrilla are anticipating.

There are several stumbling blocks to the fracking proposals. Some imply that the drilling of wells would have to be strung out over many years into the future.

There are simply not the drilling rigs in the UK at the moment to embark on a massive drilling programme. There is not the infrastructure, for example a huge number of new pipelines would need to be built, plus compressor stations, to handle the number of wells and pads envisaged. Even to properly explore and to provide new data to inspire investor confidence will require a number of wells – maybe 10 to 20 – running test production for a year or more.

So if the drilling of serious production wells won’t start for some time, and will be spread out over decades, it is clear there will be no major impact during this period on Britain’s self-sufficiency in gas. Further that we will be extending the life of wells beyond what we would expect as the lifetime of gas-burning power stations in order to satisfy our climate change commitment.

Another issue is water. It is said the fracking of each well may take 4 to 8 UK million gallons. If we assume that in the UK horizontals will have to be longer than normal in the US we can expect water use to be on the higher rather than the lower side of the estimate. Cuadrilla told the Energy and Climate Change Committee 1,000 cu m (200,000 gallons) for drilling and 12,000 cu m (2.6 million gallons) pre frack, if you prefer to believe Cuadrilla. Nick Grealy in separate evidence suggested 3 million. I will use the lower independent estimate of 4 million gallons. Each well can be fracked more than once in its lifetime to try and boost falling production rates, but there is no guide to how frequently this might happen in the UK.

That makes the usage for 3,600 wells including drilling and fracking once 14.4 billion gallons. Bearing in mind that Cuadrilla’s patch is only a fraction of the UK area now under consideration for fracking this is a serious consideration when scaled up. If we take “virtual water” into account, ie water use abroad that is used to provide our imported goods, the UK, only 38% of the UK’s water use comes from its own resources. For the sake of false energy security we are risking our water security into an uncertain future where climate change may mean that particularly poor agricultural areas of the world with more serious water problems than ourselves can no longer be relied upon to supply us with food or other products.

Large volumes of water used for fracking mean large volumes of waste returned water. And there are no plans to adequately deal with the liquid waste of fracking at the levels expected by a production phase. Water use and waste fracking fluid are only the first of the environmental considerations.